(Read the series via the live link here at toledoblade.com) Part 1 of a 3-part series. Published Dec. 6, 2020. Winner in Ohio’s Best Journalism Contest for investigative reporting. Graphics by Danielle Gamble.

By SARAH ELMS, BROOKS SUTHERLAND, and DANIELLE GAMBLE, The Blade

The sheriff’s deputies showed up while she was loading her belongings into a U-Haul.

Kytrell Brown, 40, had tried in court to fight her eviction from public housing, but she couldn’t gather all the documents she needed in time to prove the lights and gas were back in her name.

The judge sided with Lucas Metropolitan Housing, after the public housing authority said she failed to maintain the utilities, owed $46.50 in maintenance costs, and failed to fill out paperwork recertifying her for public housing.

Ms. Brown waited until the last minute to move out of the two-bedroom John Holland Estates townhome she shared with her 6-year-old son, Adryin, because she didn’t have a new place to move to. She didn’t want to have to start all over once she found an apartment, so she spent the last of her cash on the truck and a storage unit.

As the calendar approaches Jan. 1, when a national eviction moratorium meant to protect renters during the coronavirus pandemic expires, many low-income Toledoans worry they’ll end up like Ms. Brown: kicked out of public housing with no place else to go.

“I was embarrassed. I was hurt. I was scared because I didn’t have really nowhere to go. I was angry. I was afraid for my baby’s life. I was afraid for my life,” Ms. Brown said. “Like, how can you put me out right in the middle of this? We could have settled this. We didn’t have to go this far.”

A BROKEN SYSTEM

A Blade investigation found LMH filed more than 2,200 evictions against its tenants in the past five years, making it one of Lucas County’s most litigious landlords. The coronavirus made 2020 an outlier, as evictions for nonpayment of rent were paused March 27.

LMH officials said evictions are a necessary tool for removing tenants who commit crimes or disturb their neighbors. But an analysis of housing court data revealed 91 percent of their cases were for past-due rent.

What’s more, 37 percent of the nonpayment cases were filed for less than $100 owed.

Filing an eviction in Toledo Municipal Court, according to its website, costs between $107.50 and $120.50, depending on whether a landlord wants to collect back rent and damages or simply wants the tenant out. That does not include how much a landlord pays a lawyer to represent them.

And for all that paperwork, The Blade found LMH stood to collect less than $50,000 in past-due rent and fees from those small-sum cases. That’s less than 9 percent of the nearly $560,000 in total past-due amounts LMH aimed to collect through evictions in those five years.

LMH manages 2,633 public housing units, most of them in Toledo and largely rented to households led by low-income black women with children, demographic data show. Tenants pay rent based on their income, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development subsidizes the rest.

Public housing is designed as a safety net to prevent people from slipping into homelessness, or to lift them out of it. Toledo Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz, a Democrat, said Lucas County’s system isn’t working properly if families are being evicted over such small amounts of money.

“Just as a general practice, we shouldn’t be evicting people for dollar amounts smaller than the cost of filing the court papers,” he said. “Not only does it not look right, it doesn’t feel right. It just isn’t right.”

But he expressed confidence in LMH’s President and CEO Joaquin Cintron Vega, who took the helm in March, calling him a talented leader who recognizes there is a problem.

“If this is how the system works, the system is broken,” Mr. Kapszukiewicz said. “I trust that they’ll fix it.”

LMH officials defended their eviction practices in a series of Blade interviews, contending they give tenants ample notice and multiple chances to work out issues before they’re taken before a judge. LMH only uses the court process as a last resort, Mr. Vega said.

“For me, one eviction is concerning,” said Mr. Vega, who returned to Lucas County after overseeing public housing in Miami-Dade County, Fla., at the country’s seventh-largest housing authority. “When somebody loses the opportunity to remain in a place that they can call home, one is too many.”

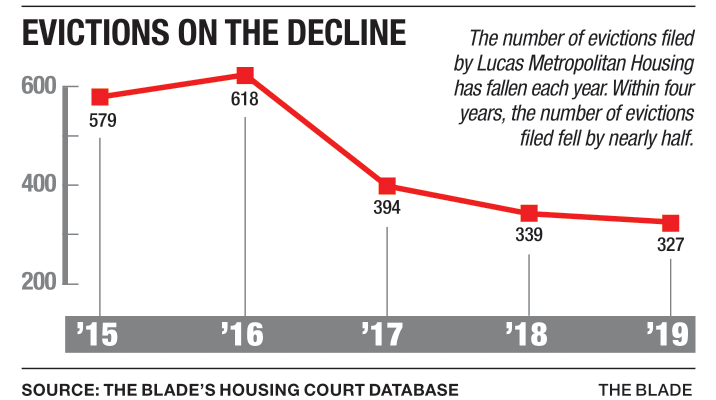

Yet records show the agency filed eviction cases against tenants more than 300 times last year – and that’s down from 2016, when they topped 600.

Housing Court data also show LMH won eviction orders in 68 percent of the cases it filed in the past five years. It’s not clear how many tenants in those cases were forced out, as LMH does not track the outcomes of their eviction cases. The dismissals include cases in which tenants moved out before their hearing date or reached last-minute settlements at the courthouse.

LMH Board President Bill Brennan said the housing authority, which gets most of its funding from the federal government, has an obligation to taxpayers to be fiscally responsible. His understanding is LMH officials do work with tenants before they take a case to court.

The Blade’s investigation has prompted him to ask if LMH can do more.

“I’m willing to put it on the agenda for the board to start discussing going forward,” he said. “It’s something I think we do need to take a look at.”

‘THIS IS LOW-INCOME’

The Blade reviewed thousands of court documents and interviewed more than 30 current or former LMH residents to understand how evictions in Lucas County’s public housing played out before and during the coronavirus pandemic.

Each person who spoke to The Blade knows well what it means when a deep-red envelope is posted on their door. They all know someone like Ms. Brown, have been under threat of eviction themselves, or have watched as bailiffs showed up to supervise the methodical transfer of a neighbor’s belongings from apartment to curb.

Eighteen of the people interviewed for this story had received the “red letter of doom,” as one LMH tenant calls it. Seven had received multiple notices on their doors in the last five years; Ms. Brown had received six. Each of them said that, in most cases, they don’t believe court action was necessary to resolve the issue.

Charlene Hughes, 37, is a single mom. Some months her expenses and income don’t quite line up, and she’ll miss a rent payment.

“They just keep on at it, and then they hurry up and try to take you to court and then hurry up and try to evict you,” she said. “This is low-income [housing]. Why would you try to evict anybody from low-income? That’s the reason why they got low-income, because they struggling.”

Last year LMH sued Ms. Hughes because she owed $50 in rent, $5 for a maintenance cost, and a $15 late-fee. She signed a “promise to pay” and got on a repayment plan for the $70, plus the court costs LMH incurred to sue her.

Ms. Hughes caught up, but it’s stressful for her to think about what would have happened to her and her 3-year-old son if she hadn’t.

“Then they’ll have you on the street,” she said. “They don’t care if you have kids.”

Five of the families who spoke to The Blade said they would have nowhere to go if evicted today. Nine said they would go stay with relatives or friends, but it wouldn’t be a permanent solution.

Before Kayla Nuzum moved into her two-bedroom LMH apartment in December 2015, she stayed at the Family House shelter in the central city. Her rent is $50 a month, the LMH minimum, and she’s usually able to pay it with the handful of hours she works at a dry cleaning shop downtown each week.

Ms. Nuzum, 32, said she tries hard to be a good tenant. Court records show LMH sued her three times between 2018 and 2019 for rent and late fees, once for $85 and twice for $50, but she paid up each time and was never set out.

She has three children and a baby on the way, and she doesn’t want to lose the home she has built for her family.

“If you put us out, where are we going to go?” Ms. Nuzum said.

When the pandemic took hold in the United States in March, the economy stalled, and unemployment levels skyrocketed. An eviction crisis housing advocates have warned about for years suddenly became top of mind.

Some relief has come in the form of stimulus checks, a government-mandated halt to most eviction cases in federally subsidized properties, and temporary changes in local housing agencies’ own policies. LMH, for example, extended an eviction moratorium through December, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded its own moratorium on certain evictions to year’s end.

Sarah Jenkins, director of public policy and community engagement for Toledo’s Fair Housing Center, said housing insecurity, particularly for low-income renters, was already at a crisis level nationally and locally before the coronavirus exacerbated the problem.

She doesn’t see that changing when the moratoriums lift, nor once the pandemic recedes.

A quarter of Toledo’s 275,000 residents live below the poverty line, according to U.S. Census estimates, and hundreds were living in emergency shelters or on the street before the pandemic hit. The need for affordable housing in Lucas County is so great that LMH’s own 2,500-person public housing waitlist stopped accepting new names in February because the authority’s inventory couldn’t meet demand.

But even then, policies were slow to change and rental assistance was hard to come by. It wasn’t until the pandemic-induced economic plunge that governments paused evictions and prioritized financial help for renters.

“These housing needs are going to continue well beyond COVID,” Ms. Jenkins said. “Hopefully this is an opportunity now that we have the eyes of the world on this issue to really get some movement on this.”

UNDER PRESSURE

Mr. Vega and other LMH officials described their job in public housing as a balancing act.

Because of a shortage of affordable housing in Toledo, there are hundreds of families on LMH’s public housing waiting list. If a current tenant isn’t meeting their lease agreement, there’s someone on the list who will, Mr. Vega said.

Public housing authorities also have to remain in good standing with HUD, the agency that provides the bulk of their funding. In 2020, HUD subsidies comprised about $40.2 million of LMH’s $57.3 million budget, or about 70 percent.

About $25 million went toward housing choice vouchers, commonly referred to as Section 8; LMH also received $2.8 million to administer the program. The other $12.4 million closed the gap between what public housing residents paid in rent, about $5.3 million in 2020, and what it costs to keep the apartments operating.

The federal government currently considers LMH a “standard performer,” but Mr. Vega’s goal is to reach a “high performer” designation because it gives the agency more financial flexibility and a leg up when it comes to competitive funding. In order to do that, LMH must maintain a high rate of occupancy and a high rate of rent collection, he said.

What’s more, the less rent LMH is collecting each month, the less money it has to cover operations and programming costs. And that’s important because the HUD subsidies are only enough for public housing authorities to keep the doors open, experts said. There isn’t enough, for example, to fund the increasing maintenance costs of aging housing or to pay for programs residents need.

HUD’s regional and national offices did not grant The Blade an interview, but a spokesman from the Chicago regional office, which oversees Ohio, in an email said housing authorities are required to collect rent based on family income.

“Not collecting rents owed reduces the funds available for operations of the agency,” spokesman Gina Rodriguez wrote.

Housing authorities are not required to report data about evictions to HUD.

“Housing authorities have an extremely difficult job to do,” said Marcus Roth, spokesman for the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio. “They’re charged with housing people dealing with extreme poverty, and housing authorities have been woefully underfunded for some time now. They still have to figure out how to make the finances work.”

Mr. Roth said he understands public housing authorities are in a tough financial position, but officials should work to enforce rent collection policies without taking renters to court.

“That puts them, really, at extremely high risk of homelessness,” he said. “They should generally do everything in their power before evicting people for nonpayment. It’s a terrible consequence.”

While LMH leadership emphasized that filing an eviction doesn’t automatically mean they’re putting a family out, tenant advocates argue that having an eviction case on your record equates to a red flag for landlords.

Plus, renters are more likely to settle for substandard housing — even unsafe situations that violate legal requirements — if a landlord is willing to overlook their eviction record, Ms. Jenkins said.

Ms. Brown’s eviction from LMH was a setback that came just as she was finding stability again.

She was denied two apartments because of her eviction record, she said, even though she had gotten a job with a steady paycheck.

Finally, after three months of couch surfing with her son, she found a place through a family connection. It’s in a decent neighborhood with a playground nearby, but Adryin misses his friends and his old school.

In her living room is a desk and chair, four throw pillows, two folding chairs, and an empty fish tank. Everything else is still in storage. Ms. Brown likes to cook, but her new kitchen is tiny. The place also only has one bedroom, so she and Adryin share a bed.

Ms. Brown has osteogenesis imperfecta, a brittle bone disease. A fall that might leave a bruise on most could leave her with broken bones. Before her eviction, she suffered a fractured foot, a cracked scapula, and a torn rotator cuff, which left her in the hospital for months and out of work.

She said she tried to figure out a way to informally resolve the utilities issue with her LMH property managers once she recovered, but they took her to court instead.

As Ms. Brown juggles work and parenting, she tries hard to make rent and still have money to put away. She’s keeping her eye out for a bigger place she could rent-to-own, and she’s looking into down-payment assistance programs.

If she can buy her own home, she’ll never have to deal with another eviction again.

“I don’t wish that on my enemy,” she said.

AN IMPERFECT SOLUTION

LMH leadership said the public housing authority has been trying to reduce its eviction filings, and it seems to be working.

Court records show LMH filed 579 evictions in 2015 and 618 in 2016, and those numbers dropped to 394, 339, and 327 for 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively.

Tom Mackin, chief legal officer for the housing authority, said those reductions are a result of better communication with residents as well as stronger partnerships with advocacy groups that connect tenants to financial coaching, job training, and mental-health resources.

He also said there is a seven-day grace period before rent is considered delinquent and a $15 late fee is charged. Tenants may be delinquent three times in a 12-month period before LMH will issue a notice to vacate.

Each notice includes an invitation to try and reach a resolution with property managers during an informal meeting. It’s only if a tenant doesn’t show up to the conference or vacate their unit and turn in their keys that LMH proceeds to court.

LMH officials maintain that the informal conferences are effective, but they do not keep complete data on how many tenants take advantage of them. They also cannot say how many of those meetings led to a resolution that stopped an eviction filing.

Residents told The Blade they either didn’t know about the conference because they stopped reading the notice once they saw how much they owed, or they chose not to go because they were skeptical it would help. Those who did attend the informal conferences reported mixed results.

One tenant, a mother of three who received a three-day notice just before Christmas in 2019, said the meeting was pointless. Alexus Boyd, 21, had been in an altercation with another resident. The police responded to the incident, but no charges were filed.

Still, Ms. Boyd, whose only criminal record in Toledo Municipal Court is a traffic ticket, got a three-day notice to vacate her Port Lawrence Homes apartment. She tried to smooth things over at her informal conference.

“When I went in to talk about it, she really didn’t want to hear it,” Ms. Boyd said of her property manager. “They were saying I still had to leave and it didn’t matter because the police were called.”

She enlisted the help of Legal Aid of Western Ohio, and her case was dismissed in court.

When a 14-day notice arrived on Taberah Israel’s door, she was confused and scared. The 32-year-old pregnant mother of four had just recently moved into LMH’s Birmingham Terrace from the Family House Shelter, and she didn’t want to go back.

“I’ve never been evicted ever. It was scary,” she said.

She went to the meeting with her property manager and learned the notice was over a misunderstanding about her security deposit. She thought a subsidy covered it, she said, but LMH told her she needed to pay. They worked out an agreement, and Ms. Israel was able to keep her eviction record clean.

Ms. Brown said the first time she received a notice to vacate, the informal conference worked. She had failed to fill out her recertification form properly, but she met with the property manager and worked it out without an eviction filing.

She was able to resolve the next five evictions over late rent payments, too, but only after going to court. This summer, the process wasn’t as effective. She said she tried to work with management, but she was set out in June.

Court records show an attorney from Legal Aid of Western Ohio argued LMH should not be allowed to conduct the eviction, since the CARES Act prohibited them from March 27 through July 24. But the judge ruled that because a judgment was reached in favor of LMH on Feb. 28, before the CARES Act was put in place, Ms. Brown’s eviction could proceed.

“I believe that you’re supposed to pay your bills, OK?” Ms. Brown said. “But if life happens and there is a dire situation, then have some compassion. Work with that person.”

ABOUT THIS THREE-PART SERIES

Lucas Metropolitan Housing is among the city’s top landlords when it comes to eviction filings. The Blade set out to determine why that is, who is most impacted by it, and what can be done about it.

We conducted this investigation in partnership with the Investigative Editing Corps, founded in 2017 by Pulitzer Prize-winning editor Rose Ciotta, which pairs experienced investigative editors with local newsrooms.

This three-part series was produced by (pictured above, from left) Blade reporters Sarah Elms and Brooks Sutherland, photojournalist Amy E. Voigt, digital journalist Danielle Gamble, and reporter Ellie Buerk. It was edited by Deborah Nelson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and professor of investigative journalism at University of Maryland; Sean Mussenden, data editor for University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism; Kim Bates, The Blade’s managing editor; and Mike Walton, The Blade’s city editor.